Jeroen Kraaijenbrink is an accomplished strategy educator, mentor, author, and consultant with over two decades of academic and industry experience. He empowers people and organizations to design, formulate, and execute their strategies by providing innovative tools for forward-thinking strategy and personal and organizational development. Drawing from cognitive psychology, humanism, martial arts, Saint Benedict, and a wide range of other sources, he has written innumerable articles on strategy, sustainability, and leadership, as well as authored five books: Strategy Consulting, No More Bananas, Unlearning Strategy, The Strategy Handbook, and The One-Hour Strategy. He is also a contributor to Forbes and a LinkedIn influencer, where he writes about strategy and leadership. Jeroen has a PhD in industrial management, teaches at the University of Amsterdam, is co-founder of Strategy.Inc, and has helped significantly improve the strategic planning of many organizations across the engineering, manufacturing, healthcare, and financial services industries.

Failure rates in strategy remain uncomfortably high, decade after decade. Depending on how success and failure are defined, some speak of 40-50% failure, others even of 70-90%. Whatever the exact percentage, the rates are too high. For any other aspect of business, we would not accept such high failure rates. So why should we for strategy? We shouldn’t. There is no need for this because the reasons for failure are clear—as are their solutions.

The Threefold Watershed Between Strategy and Execution

Years of research by many scholars across the globe reveals numerous factors contributing to strategy failure. Comparing these factors from one study to the other, it appears they are remarkably consistent over time. This means the problems and causes are known.

Largely they boil down to the following three. First, strategy has long been conceptualized as a linear, lengthy process with strategy formulation first and, once finished, followed by execution. This linear approach to strategy is still often the default that is taught and practiced. It rejects the close interaction between strategy formulation and execution and the iterative, adaptive nature of strategy by separating formulation and execution over time.

Second, strategy and execution are usually also separated within the organizational structure. Strategy is often formulated at and by the top, after which it is supposed to trickle down to lower levels, ending up at the level of individual employees. This organizational split makes it hard to be successful in strategy because those who know the day-to-day reality are not involved in strategy formulation, while those at the top stay out of execution.

Third, strategy is often made into something special, exceptional. This is clearest in off-sites and so-called “strategy days.” These are often literately separated from the normal business by organizing them at a nice resort, and deliberately taking people away from their everyday work. While often presented as a strength, this creates a third split between strategy and everyday business.

In essence, all three boil down to one key problem: we’ve created a systematic, threefold watershed between strategy formulation and execution. Diagnosing this problem immediately tells us what the solution is: removing the watershed and restoring the connection between the two an all three aspects. The pressing question now is: how?

Moving Forward: Strategy as Everyone’s Everyday Business

In my most recent book, The One-Hour Strategy, I give an extensive, 100-page answer to this question, packaged into a simple story. But the short version isn’t too complicated either. At the core of it are three main steps.

Step 1: Adopt a Single Strategizing Framework at All Levels

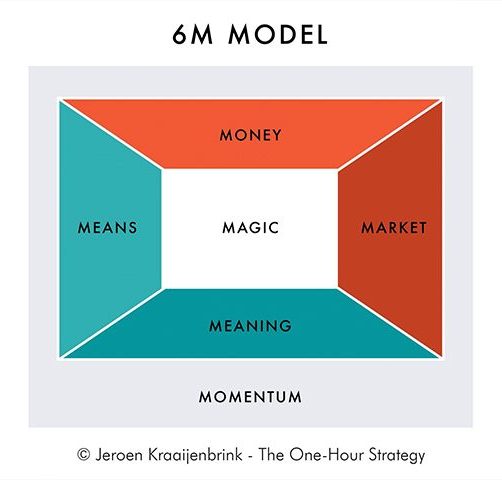

The first thing you need is unity in understanding what strategy is all about and how you approach it. You need a shared language and strategy framework that can be applied at all levels: corporate, business, functional, team and individual level. My own model for this is the 6M Model, consisting of 6 key elements (see figure):

- The products and services that we offer and what they do for our customers.

- The customers whose needs we serve and the alternatives we compete against.

- The assets and capabilities that we and our partners can bring to the table.

- The way and amount of revenues we generate versus the costs and risks we have.

- The things that we find most important and to which we most aspire.

- The factors outside our control that help or hinder us in what we do.

At any level, people can use this model to diagnose their existing strategies, as well as design their aspired strategies and identify initiatives for improvement.

Step 2: Create a Continuous Strategy Process at Each Level

Once there is a shared view on what strategy is, the next step is to create a systematic strategy process that clarifies what people need to do when. To start with, it helps to indicate how much time people should spend on strategy. The rule of thumb I adopt in The One-Hour Strategy is that executives work on it one hour per day, managers one our per week and employees one hour per month.

Subsequently, you define what people are supposed to do during this time, preferably in the form of a continuous, cyclical process, for example:

- Identify key issues, insights and ideas for each of the six Ms.

- Prioritize which of these to focus on the coming period.

- Define one or more initiatives to address the selected issues, insights, or ideas.

- Execute the initiatives and monitor their relevance, progress and mood.

And then repeat these four steps throughout the year on a daily, weekly or monthly basis.

Step 3: Mutually Align Strategies Horizontally and Vertically

The previous two steps support systematic, everyday strategy generation and execution at all levels. What is still missing is the alignment between the sub-strategies. We need that alignment because we want an organization to function as one coherent whole, not as a fragmented set of business units, departments or divisions. Dependent on how hierarchical an organization is, there are different routes for this:

- Top-down. Executives work on their corporate level strategy first, which then cascades down and serves as input for strategy making further down the organization.

- Bottom-up. Units first work on their own strategies and circle it upwards to the corporate level where the corporate strategy is abstracted and generalized from the unit’s strategies.

- Units mutually align with each other. They circle their strategies back and forth between them and use these as each other’s input.

While the first is most common, all three are valid. What matters is that you create a continuous horizontal and vertical feedback and feedforward process.

This cannot succeed at once. But that is not the point. What counts is that, in this way, we are step-by-step establishing a systematic, everyday strategy process across the entire organization. And that is what we need to remove the threefold watershed, reconnect strategy and execution, and finally increase strategy’s success rates.